A lone traveler stands beneath the towering yew tree in the churchyard of Nevern, Pembrokeshire. The air is thick with the scent of damp earth and resin, and the soft hush of wind through the branches is the only sound. A second figure stands beside them, clothed in a long woolen cloak, feet calloused from the road, eyes bright with devotion. Though centuries separate them, they see the same sacred place, feel the same weight of history pressing on their shoulders.

“Do you see?” The medieval pilgrim gestures toward the Bleeding Yew, the deep red sap weeping from its bark. “They say it bleeds for justice, and it will not stop until the world is fair.” Their voice is heavy with belief.

The modern visitor runs a hand over the rough bark, watching the slow seep of crimson. “I’ve read about it—some say it’s just a natural phenomenon, something about the tree’s resin reacting to wounds. But still… standing here, it feels like more than that.” They hesitate, then add, “Maybe it does bleed for something. Maybe it always will.”

The pilgrim nods, satisfied. “Come. There is more to take in.”

Together, they walk toward the Great Celtic Cross, its weathered stone rising 13 feet defiantly into the sky. The pilgrim reaches out, tracing the loops and knots carved into its surface. “This is eternity,” they murmur. “No beginning, no end. Just faith, winding on forever.”

The visitor studies the carvings, fingers brushing lightly over the stone. “It’s amazing. To think of the hands that made this, how many people must have stood before it, just like we are now. Even after all this time, it still stands.”

“As it should,” the pilgrim replies. “A signpost for those on the road to St David’s. A beacon for the weary pilgrim.”

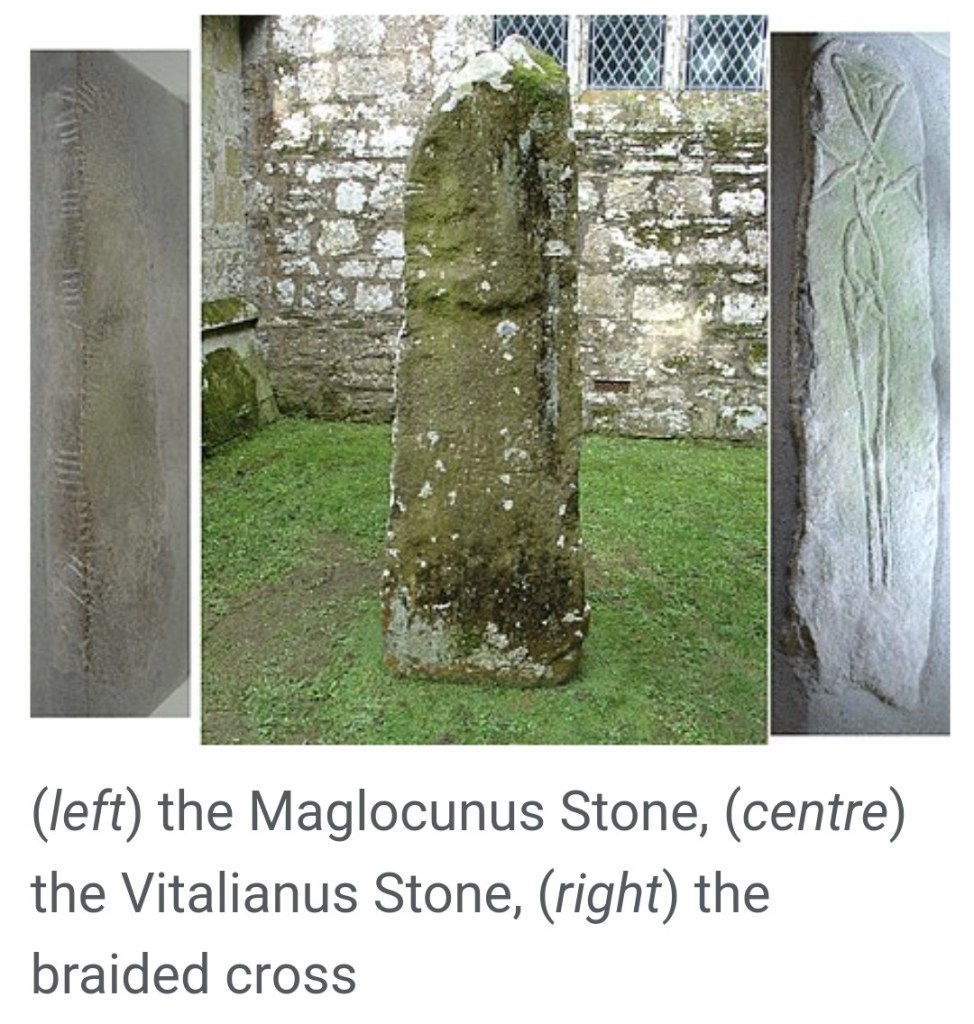

Just outside the church. The Vitalianus Stone, carved into a pillar in Ogham and Latin the words “VITALIANI EMERTO” suggests the resting place of an important man named Vitaliani. The two languages hint at ancient connections between pagans and Christians. Its inscriptions whispering secrets from the past that we may never understand. The pilgrim kneels before it, tracing the letters. “He was a leader once, a man of faith and strength. His name endures in stone, even as his body has long turned to dust.”

The visitor leans in, examining the Latin and Ogham script. “It’s strange. We carve our names into things, thinking it will make us last forever. But in the end, it’s the stories that survive, not the physical marks.”

The pilgrim smiles. “You understand.”

Inside the church, cool air wraps around them, thick with the scent of wax and old stone. On one of the windowsills, they see the Megalocnus Stone, where the marks of the older tongue carve deep into the rock. Megalocnus is referenced as far back as the sixth century, affirming the stone’s age. The visitor shakes their head in wonder. “This writing—Ogham—it’s like the language of the land itself, growing up from the stone.”

The pilgrim rests a hand against it. “We mark the world, and the world marks us.”

On another windowsill, they find the Pilgrim’s Cross, shallowly etched into the stone. The modern visitor touches the carving, feeling its rough edges. “So many hands must have traced this over the years.”

“I made my own mark,” the pilgrim admits, voice quiet. “And those after me, and those after them. We all do. All hoping to pass through life, to the next, peacefully.”

They pause before the Norman-era Rood Screen, its carved wood forming a delicate boundary between the sacred and the earthly. The visitor runs their hand along its surface. “It’s so intricate. So much work must have gone into this.”

“Devotion is in the small detail as well as the bigger view,” the pilgrim replies. “In all things, we find the divine.”

At the 700 year old Medieval Baptismal Font, the pilgrim dips their fingers, letting the cool water trickle over their skin. “A new beginning,” they whisper.

The visitor hesitates, then does the same. The water is cold against their fingertips, sending a shiver through them. “Some things never change,” they murmur.

Outside, the old Sundial catches the last light of the afternoon. The visitor laughs softly. “Hundreds of years ago, someone stood right here, checking the time by the same sun we’re looking at now.”

The pilgrim nods. “And after another thousand, others will do the same.”

A short walk uphill leads them to the second Pilgrim’s Cross, carved deep into the rock behind the church. The view stretches below them, the land rolling away toward the river. The pilgrim kneels, bowing their head in prayer.

The visitor stands in silence, breathing in the crisp air. “It must have been hard,” they say at last. “Walking so far, carrying all your hopes with you.”

The pilgrim exhales, voice full of quiet conviction. “Hope is never a burden. It is the reason we walk.”

As they walk toward the ruins of Nevern Castle, the shadows grow long. The stones stand witness to battles and prayers lingering in the air.

“Time is strange here,” the visitor muses. “It doesn’t feel like it’s passing. It just… is.”

The pilgrim smiles. “At Nevern, time doesn’t pass—it pools around your feet.”

The modern traveller, now seeped in the church’s history, looking down to their feet, feels a pull to join the age-old pilgrimage. Looking up, they see the ancient pilgrim is making their way–fading into the distance. “God bless!”

Your support makes a difference in my life and helps me create more of what you, and I, like. Thank you!

- Darkness, Power and Beauty

Horse’s steady gazeStrengthful eyes that dare to meetChallenge accepted Courage is the strength to face… Read more: Darkness, Power and Beauty

Horse’s steady gazeStrengthful eyes that dare to meetChallenge accepted Courage is the strength to face… Read more: Darkness, Power and Beauty - The Daffodil’s Song: A Lyrical Tribute to the Wonders of Spring

Daffodil so brightGolden petals, sunshine’s kissHope blooms anew As I wander through the garden, the… Read more: The Daffodil’s Song: A Lyrical Tribute to the Wonders of Spring

Daffodil so brightGolden petals, sunshine’s kissHope blooms anew As I wander through the garden, the… Read more: The Daffodil’s Song: A Lyrical Tribute to the Wonders of Spring - Acanthus: A Versatile Plant with a Rich Cultural Heritage

The Graceful Lines of an Acanthus Leaf. Acanthus is a genus of flowering plants native… Read more: Acanthus: A Versatile Plant with a Rich Cultural Heritage

The Graceful Lines of an Acanthus Leaf. Acanthus is a genus of flowering plants native… Read more: Acanthus: A Versatile Plant with a Rich Cultural Heritage

You must be logged in to post a comment.