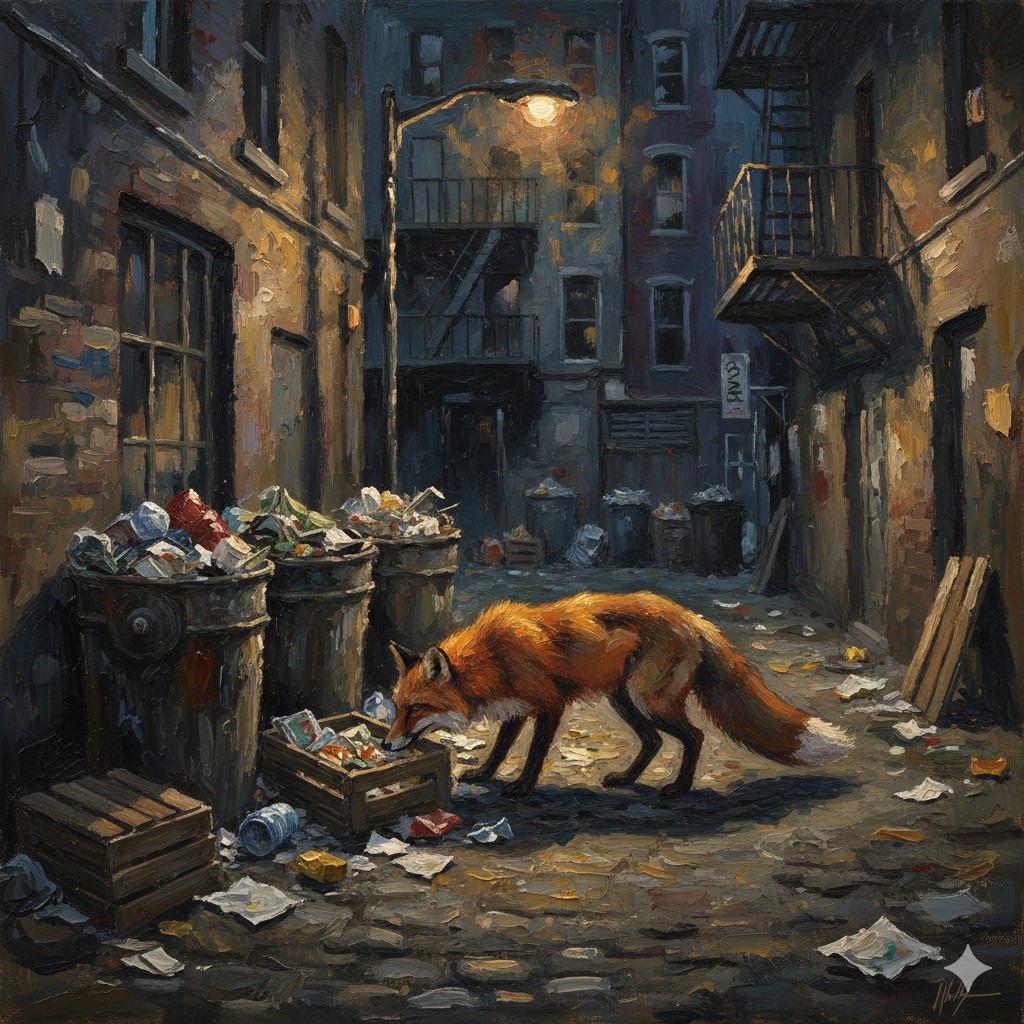

Rust-red coat dulled—

streetlight bleeds sodium gold.

Fox: smoke, not ghost.

The fox moves through the alley like smoke round iron bars – low, deliberate, unseen. Her coat, once red as autumn leaves, has dulled to the colour of rust and old blood. The city does that to things. Takes the bright and makes it grey.

She stops at the mouth of the alley where it opens onto Bethnal Green Road, nose testing the wind. Diesel fumes. Rotting produce from the day’s market. Something dead in a skip three blocks over. And underneath it all, the scent of prey – rats moving through the Victorian sewers like criminals through tunnels.

The streetlights flicker on, casting everything in sodium orange. She waits. Patience is survival here, just like it was in the countryside before the housing estates came, before her mother’s den became someone’s foundation. The city is just another territory. Meaner. Colder. But still just earth and concrete, and she knows how to read both.

A drunk stumbles past, muttering to himself. The fox presses herself against the brick, invisible. She’s learnt early that humans are dangerous in their unpredictability – sometimes they throw things, sometimes they feed you, sometimes they just stare like you’re a ghost. She prefers to be the ghost.

She crosses the street in the space between heartbeats, a shadow amongst shadows. Past the shuttered pawnbroker’s with its cage of forgotten promises. Past the council block where someone is always screaming and someone is always crying and someone is always turning up the telly to drown them both out. Past the church with broken windows like missing teeth.

The wheelie bin behind the chicken shop is her destination tonight. Tuesday nights they throw out the weekend’s failures. She times it, has learnt it, the way her ancestors learnt the movement of rabbits through meadows. Everything is a pattern if you watch long enough.

She noses through the bags with practised efficiency. Chicken bones, mostly stripped but with enough meat to matter. Half a container of rice, cold and congealed but calories nonetheless. She eats quickly, always listening, always watching. In the city, you eat like you might never eat again. Because sometimes you don’t.

A siren wails somewhere towards Hackney. The fox lifts her head, ears swivelling. Not her problem. Not tonight.

She moves on, through territories marked by other foxes, other survivors. Past the rough sleeper in a cardboard fortress who mumbles blessings at her as she passes. Past the dealer on the corner who sees her every night and has stopped being surprised. Past windows full of people staring at screens, blue light turning their faces into masks.

At the park – if you can call it a park, this patch of dying grass and one exhausted plane tree – she pauses. This is as close to home that she has. A culvert beneath the footpath, dry in summer, tolerable in winter. Safe. Hidden. Hers.

She slips inside and curls into herself, tail over nose. Outside, the city growls and hums and never sleeps. Car alarms. Distant arguments. The eternal rumble of traffic on the North Circular, that river of metal and light that never stops flowing.

She closes her eyes but doesn’t sleep. Not yet. In the city, you sleep light or you don’t wake up.

Tomorrow night she’ll do it all again. Hunt the same streets, raid the same bins, ghost through the same alleys. The city is a maze with no exit, a trap that feeds you just enough to keep you walking its endless circuits.

But she’s still here. Still moving. Still breathing.

In the city, that’s something close to winning.

Your support makes a difference in my life and helps me create more of what you, and I, like. Thank you!

Tap here for a list of 100 endangered animals and plants.

100 endangered plant and animal species

* Abies beshanzuensis (Baishan fir) – Plant (Tree) – Baishanzu Mountain, Zhejiang, China – Three mature individuals

* Actinote zikani – Insect (butterfly) – Near São Paulo, Atlantic forest, Brazil – Unknown numbers

* Aipysurus foliosquama (Leaf scaled sea-snake) – Reptile – Ashmore Reef and Hibernia Reef, Timor Sea – Unknown numbers * Amanipodagrion gilliesi (Amani flatwing) – Insect (damselfly) – Amani-Sigi Forest, Usamabara Mountains, Tanzania – < 500 individuals * Antisolabis seychellensis – Insect – Morne Blanc, Mahé island, Seychelles – Unknown numbers * Antilophia bokermanni (Araripe manakin) – Bird – Chapado do Araripe, South Ceará, Brazil – 779 individuals * Aphanius transgrediens (Aci Göl toothcarp) – Fish – south-eastern shore of former Lake Aci, Turkey – Few hundred pairs * Aproteles bulmerae (Bulmer’s fruit bat) – Mammal – Luplupwintern Cave, Western Province, Papua New Guinea – 150 * Ardea insignis (White bellied heron) – Bird – Bhutan, North East India and Myanmar – 70–400 individuals * Ardeotis nigriceps (Great Indian bustard) – Bird – Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Madhya, India – 50–249 mature individuals * Astrochelys yniphora (Ploughshare tortoise) – Reptile – Baly Bay region, northwestern Madagascar – 440–770 * Atelopus balios (Rio Pescado stubfoot toad) – Amphibian – Azuay, Cañar and Guyas provinces, south-western Ecuador – Unknown numbers * Aythya innotata (Madagascar pochard) – Bird – volcanic lakes north of Bealanana, Madagascar – 80 mature individuals * Azurina eupalama (Galapagos damsel fish) – Fish – Unknown numbers – Unknown numbers * Bahaba taipingensis (Giant yellow croaker) – Fish – Chinese coast from Yangtze River, China to Hong Kong – Unknown numbers * Batagur baska (Common batagur) – Reptile (turtle) – Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia and Malaysia – Unknown numbers * Bazzania bhutanica – Plant – Budini and Lafeti Khola, Bhutan – 2 sub-populations * Beatragus hunteri (Hirola) – Mammal (antelope) – South-east Kenya and possibly south-west Somalia – < 1,000 individuals * Bombus franklini (Franklin’s bumblebee) – Insect (bee) – Oregon and California – Unknown numbers * Brachyteles hypoxanthus (Northern muriqui / Woolly spider monkey) – Mammal (primate) – Atlantic forest, south-eastern Brazil – < 1,000 * Bradypus pygmaeus (Pygmy three-toed sloth) – Mammal – Isla Escudo de Veraguas, Panama – < 500 * Callitriche pulchra – Plant (freshwater) – pool on Gavdos, Greece – Unknown numbers * Calumma tarzan (Tarzan’s chameleon) – Reptile – Anosibe An’Ala region, eastern Madagascar – < 100 * Cavia intermedia (Santa Catarina’s guinea pig) – Mammal (rodent) – Moleques do Sul Island, Santa Catarina, Brazil – 40–60 * Cercopithecus roloway (Roloway guenon) – Mammal (primate) – Côte d’Ivoire – Unknown numbers * Coleura seychellensis (Seychelles sheath-tailed bat) – Mammal (bat) – Two small caves on Silhouette and Mahé, Seychelles – < 100 * Cryptomyces maximus (Willow blister) – Fungi – Pembrokeshire, United Kingdom – Unknown numbers * Cryptotis nelsoni (Nelson’s small-eared shrew) – Mammal (shrew) – Volcán San Martín Tuxtla, Veracruz, Mexico – Unknown numbers * Cyclura collei (Jamaican iguana / Jamaican rock iguana) – Reptile – Hellshire Hills, Jamaica – Unknown numbers * Daubentonia madagascariensis (Aye-aye) – Mammal (primate) – Deciduous forest, East Madagascar – Unknown numbers * Dendrophylax fawcettii (Cayman Islands ghost orchid) – Plant (orchid) – Ironwood Forest, George Town, Grand Cayman – Unknown numbers * Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (Sumatran rhino) – Mammal (rhino) – Sabah, Sarawak and Peninsular Malaysia, Kalimantan and Sumatra, Indonesia – < 100 (more recent estimates suggest 34-47) * Diomedea amsterdamensis (Amsterdam albatross) – Bird – Breeds on Plateuau des Tourbières, Amsterdam Island, Indian Ocean. – 100 mature individuals * Dioscorea strydomiana (Wild yam) – Plant – Oshoek area, Mpumalanga, South Africa – 200 * Diospyros katendei – Plant (tree) – Kasyoha-Kitomi Forest Reserve, Uganda – 20 individuals in a single population * Dipterocarpus lamellatus – Plant (tree) – Siangau Forest Reserve, Sabah, Malaysia – 12 individuals * Discoglossus nigriventer (Hula painted frog) – Amphibian – Hula Valley, Israel – Unknown numbers * Dombeya mauritiana – Plant – Mauritius – Unknown numbers * Elaeocarpus bojeri (Bois Dentelle) – Plant (tree) – Grand Bassin, Mauritius – < 10 individuals * Eleutherodactylus glandulifer (La Hotte glanded frog) – Amphibian – Massif de la Hotte, Haiti – Unknown numbers * Eleutherodactylus thorectes (Macaya breast-spot frog) – Amphibian – Formon and Macaya peaks, Masif de la Hotte, Haiti – Unknown numbers * Eriosyce chilensis (Chilenito (cactus)) – Plant – Pta Molles and Pichidungui, Chile – < 500 individuals * Erythrina schliebenii (Coral tree) – Plant – Namatimbili-Ngarama Forest, Tanzania – < 50 individuals * Euphorbia tanaensis – Plant (tree) – Witu Forest Reserve, Kenya – 4 mature individuals * Eurynorhyncus pygmeus (Spoon-billed sandpiper) – Bird – Breeds in Russia, migrates along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway to wintering grounds in India, Bangladesh and Myanmar – 100 breeding pairs * Ficus katendei – Plant – Kasyoha-Kitomi Forest Reserve, Ishasha River, Uganda – < 50 mature individuals * Geronticus eremita (Northern bald ibis) – Bird – Breeds in Morocco, Turkey and Syria. Syrian population winters in central Ethiopia. – About 3000 individuals * Gigasiphon macrosiphon – Plant (flower) – Kaya Muhaka, Gongoni and Mrima Forest Reserves, Kenya, Amani Nature Reserve, West Kilombero Scarp Forest Reserve, and Kihansi Gorge, Tanzania – 33 * Gocea ohridana – Mollusc – Lake Ohrid, Macedonia – Unknown numbers * Heleophryne rosei (Table mountain ghost frog) – Amphibian – Table Mountain, Western Cape Province, South Africa – Unknown numbers * Hemicycla paeteliana – Mollusc (land snail) – Jandia peninsula, Fuerteventura, Canary Islands – Unknown numbers * Heteromirafa sidamoensis (Liben lark) – Bird – Liben Plains, southern Ethiopia – 90–256 * Hibiscadelphus woodii – Plant (tree) – Kalalau Valley, Hawaii – Unknown numbers * Hucho perryi (Sakhalin taimen) – Fish – Russian and Japanese rivers, Pacific Ocean between Russia and Japan – Unknown numbers * Johora singaporensis (Singapore freshwater crab) – Crustacean – Bukit Timah Nature Reserve and streamlet near Bukit Batok, Singapore – Unknown numbers * Lathyrus belinensis (Belin vetchling) – Plant – Outskirts of Belin village, Antalya, Turkey – < 1,000 * Leiopelma archeyi (Archey’s frog) – Amphibian – Coromandel peninsula and Whareorino Forest, New Zealand – Unknown numbers * Lithobates sevosus (Dusky gopher frog) – Amphibian – Harrison County, Mississippi, USA – 60–100 * Lophura edwardsi (Edwards’s pheasant) – Bird – Quang Binh, Quang Tri and Thua Thien-Hue, Viet Nam – Unknown numbers * Magnolia wolfii – Plant (tree) – Risaralda, Colombia – 3 * Margaritifera marocana – Mollusc – Oued Denna, Oued Abid and Oued Beth, Morocco – < 250 * Moominia willii – Mollusc (snail) – Silhouette Island, Seychelles – < 500 * Natalus primus (Cuban greater funnel eared bat) – Mammal (bat) – Cueva La Barca, Isle of Pines, Cuba – < 100 * Nepenthes attenboroughii (Attenborough’s pitcher plant) – Plant – Mount Victoria, Palawan, Philippines – Unknown numbers * Nomascus hainanus (Hainan black crested gibbon) – Mammal (primate) – Hainan Island, China – 20 * Neurergus kaiseri (Luristan newt) – Amphibian – Zagros Mountains, Lorestan, Iran – < 1,000 * Oreocnemis phoenix (Mulanje red damsel) – Insect (damselfly) – Mulanje Plateau, Malawi – Unknown numbers * Pangasius sanitwongsei (Pangasid catfish) – Fish – Chao Phraya and Mekong basins in Cambodia, China, Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam – Unknown numbers * Parides burchellanus – Insect (butterfly) – Cerrado, Brazil – < 100 * Phocoena sinus (Vaquita) – Mammal (porpoise) – Northern Gulf of California, Mexico – 12 * Picea neoveitchii (Type of spruce tree) – Plant (tree) – Qinling Range, China – Unknown numbers * Pinus squamata (Qiaojia pine) – Plant (tree) – Qiaojia, Yunnan, China – < 25 * Poecilotheria metallica (Gooty tarantula / Metallic tarantula / Peacock tarantula / Salepurgu) – Spider – Nandyal and Giddalur, Andhra Pradesh, India – Unknown numbers * Pomarea whitneyi (Fatuhiva monarch) – Bird – Fatu Hiva, Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia – 50 * Pristis pristis (Common sawfish) – Fish – Coastal tropical and subtropical waters of Indo-Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Currently largely restricted to northern Australia – Unknown numbers * Hapalemur simus (Greater bamboo lemur) – Mammal (primate) – Southeastern and southcentral rainforests of Madagascar – 500 * Propithecus candidus (Silky sifaka) – Mammal (primate) – Maroantsetra to Andapa basin, and Marojeju Massif, Madagascar – 100–1,000 * Psammobates geometricus (Geometric tortoise) – Reptile – Western Cape Province, South Africa – Unknown numbers * Pseudoryx nghetinhensis (Saola) – Mammal – Annamite mountains, on the Viet Nam – PDR Laos border – Unknown numbers * Psiadia cataractae – Plant – Mauritius – Unknown numbers * Psorodonotus ebneri (Beydaglari bush-cricket) – Insect – Beydaglari range, Antalaya, Turkey – Unknown numbers * Rafetus swinhoei (Red River giant softshell turtle) – Reptile – Hoan Kiem Lake and Dong Mo Lake, Viet Nam, and Suzhou Zoo, China – 3 * Rhinoceros sondaicus (Javan rhino) – Mammal (rhino) – Ujung Kulon National Park, Java, Indonesia – < 100 * Rhinopithecus avunculus (Tonkin snub-nosed monkey) – Mammal (primate) – Northeastern Vietnam – < 200 * Rhizanthella gardneri (West Australian underground orchid) – Plant (orchid) – Western Australia, Australia – < 100 * Rhynchocyon spp. (Boni giant sengi) – Mammal – Boni-Dodori Forest, Lamu area, Kenya – Unknown numbers * Risiocnemis seidenschwarzi (Cebu frill-wing) – Insect (damselfly) – Rivulet beside the Kawasan River, Cebu, Philippines – Unknown numbers * Rosa arabica – Plant – St Katherine Mountains, Egypt – Unknown numbers, 10 sub-populations * Salanoia durrelli (Durrell’s vontsira) – Mammal (mongoose) – Marshes of Lake Alaotra, Madagascar – Unknown numbers * Santamartamys rufodorsalis (Red crested tree rat) – Mammal (rodent) – Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia – Unknown numbers * Scaturiginichthys vermeilipinnis (Red-finned blue-eye) – Fish – Edgbaston Station, central western Queensland, Australia – 2,000–4,000 * Squatina squatina (Angel shark) – Fish – Canary Islands – Unknown numbers * Sterna bernsteini (Chinese crested tern) – Bird – Breeding in Zhejiang and Fujian, China. Outside breeding season in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand. – < 50 * Syngnathus watermeyeri (Estuarine pipefish) – Fish – Kariega Estuary to East Kleinemonde Estuary, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa – Unknown numbers * Tahina spectabilis (Suicide palm / Dimaka) – Plant – Analalava district, north-western Madagascar – 90 * Telmatobufo bullocki (Bullock’s false toad) – Amphibian (frog) – Nahuelbuta, Arauco Province, Chile – Unknown numbers * Tokudaia muenninki (Okinawa spiny rat) – Mammal (rodent) – Okinawa Island, Japan – Unknown numbers * Trigonostigma somphongsi (Somphongs’s rasbora) – Fish – Mae Khlong basin, Thailand – Unknown numbers * Valencia letourneuxi – Fish – Southern Albania and Western Greece – Unknown numbers * Voanioala gerardii (Forest coconut) – Plant – Masoala peninsula, Madagascar – < 10 * Zaglossus attenboroughi (Attenborough’s echidna) – Mammal – Cyclops Mountains, Papua Province, Indonesia – Unknown numbers

- Darkness, Power and Beauty

Horse’s steady gazeStrengthful eyes that dare to meetChallenge accepted Courage is the strength to face… Read more: Darkness, Power and Beauty

Horse’s steady gazeStrengthful eyes that dare to meetChallenge accepted Courage is the strength to face… Read more: Darkness, Power and Beauty - The Daffodil’s Song: A Lyrical Tribute to the Wonders of Spring

Daffodil so brightGolden petals, sunshine’s kissHope blooms anew As I wander through the garden, the… Read more: The Daffodil’s Song: A Lyrical Tribute to the Wonders of Spring

Daffodil so brightGolden petals, sunshine’s kissHope blooms anew As I wander through the garden, the… Read more: The Daffodil’s Song: A Lyrical Tribute to the Wonders of Spring - Acanthus: A Versatile Plant with a Rich Cultural Heritage

The Graceful Lines of an Acanthus Leaf. Acanthus is a genus of flowering plants native… Read more: Acanthus: A Versatile Plant with a Rich Cultural Heritage

The Graceful Lines of an Acanthus Leaf. Acanthus is a genus of flowering plants native… Read more: Acanthus: A Versatile Plant with a Rich Cultural Heritage

You must be logged in to post a comment.